This is an incomplete book of the sea. Felted and decorated with tinnie yolks, which I’ve had in my plastic collection for a long long time, and fastened with the plastic shaft of a cotton bud, which used to be the most commonly found marine plastic on local shores before they were replaced with paper shafts in 2019. I’m taking it with me on the ferry from Liverpool to Douglas to invite other passengers to fill it. It’s part of the AHRC funded project alinging the work of Malcolm Lowry with contemporary concerns for the ocean, Hear Us O Lord From Heaven Thy Dwelling Place, with Leeds Beckett and Liverpool John Moore’s Universities.

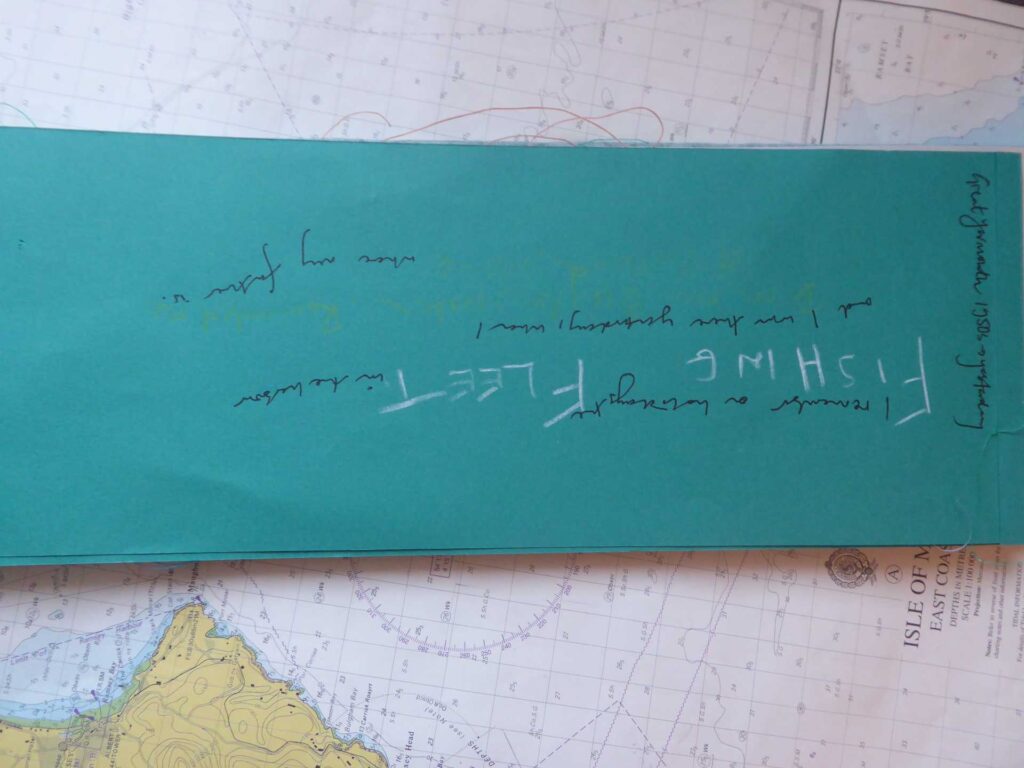

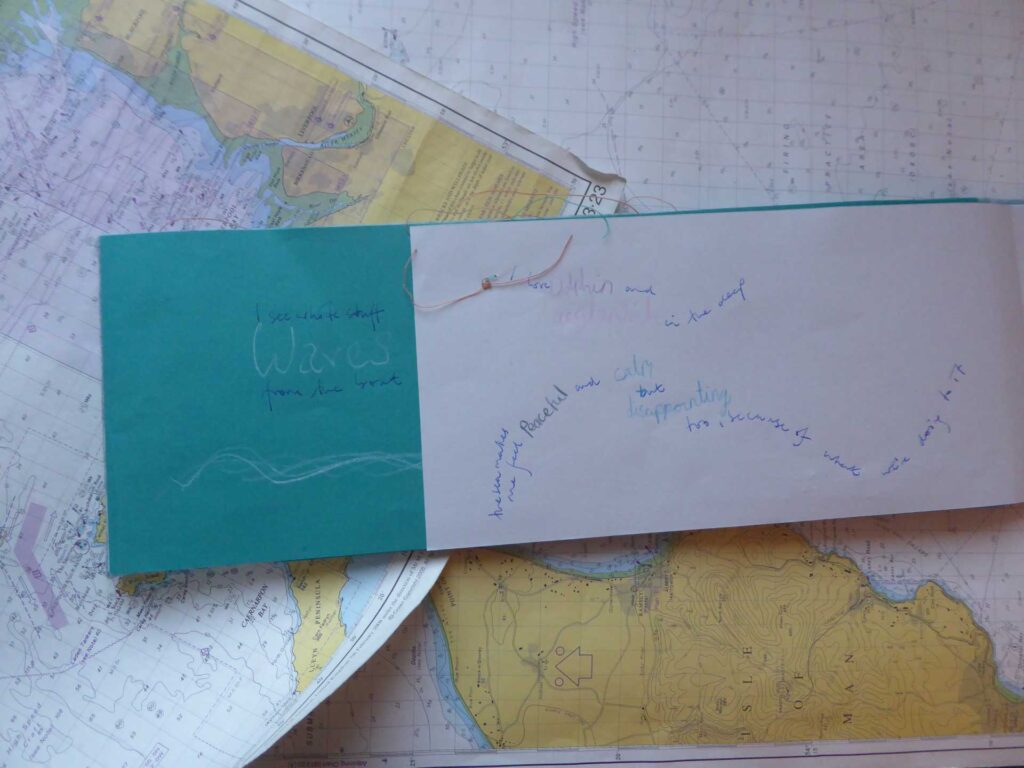

At the moment it is full of blank interleaved pages that will, hopefully, by the time we reach Douglas, thoughts, feelings and memories of the sea from other passengers. Having made the book I was suddenly reminded of those autograph books we used to take to our last day of school to be filled with verses and signatures by people, which I loved: both writing in other people’s and collecting new verses.

I’ve got inks and brushes and stamps and pens and letraset for people to use to make marks, splodge and spill and write and draw their feelings and experiences and hopes and fears for the ocean. We’ll see what gets used, what gets written and how.

Having made the book I was reminded of those autograph books we used to take to our last day of school to be filled with verses and signatures by people, which I loved: both writing in other people’s and collecting new verses. This book might become an autograph book for the sea, I thought, filled with people’s wishes and blessings for it. As soon as we’d left the Mersey channel and turned into the Irish Sea, I tucked it under my arm, stashed a pencil case in my coat pocket and headed out on deck to find people with the time to spare to chat.

People were surprisingly receptive when I bounded up to them and asked if I could talk to them. Yes, they always said, with wariness to enthusiasm.

About the sea, I’d say. I’m making a book of the sea. And given the sea has so many creatures in it I want to populate the book with as many people as possible. At which point I’d wave the book, open it and let the pages spill out between the covers.

Whoever I’d approached would generally try to gather up the pages while I asked what memories or feelings or thoughts they had about the sea. It didn’t take long for them to open up: stories of holidays, relaxation, family members, of refugees, things found, things lost, strange sea creatures, the plastic and damage we’re doing to it. Everyone had something to say about the sea.

One group I approached I told there were as many organisms in a bucket of sea water as stars in the milky way. ‘I doubt that,’ one of them said. ‘I’m a physicist and there are trillions of stars in the milky way.’ ‘Consider the viruses and bacteria as well as all the plankton, I suggested. ‘And phages,’ he says. ‘Yes,’ I agree, ‘the phages.’ Before asking what they are. The most common biological entities in nature, he tells me. And writes the word greens into the book. I wished he’d written ‘phages’. He explained he chose ‘greens’ because of all the variations in the sea. His friend, who’d been listening, then told me how when he lived in Brighton he’d swim home from work every Wednesday whatever the weather, his suit bobbing in his dry bag behind him. And then kindly wrote the entire story out into the book.

Many people were happier talking than writing, so I decided it was perhaps easier if they wrote one word down and then told me why they’d chosen it and I’d write that around the word. My process changed over the three hours of the voyage, how approached people, how I cajoled them into writing in the book, how I wrote in it. And this feels central to the intervention – adaptation to environment, to others in the environment, to hold onto the aspiration for the book, but to be loose enough with it, to want to be as inclusive as possible and respond to who I spoke to rather than impose my method onto them.

Nobody abused their power of holding pen to paper. Nobody told me to f*** off. Everybody had something to say about the water through which we were crossing. And once they started they generally were away for minutes.

I enjoyed all the takes on our ocean. How precious it is, how dangerous, threatening, and under threat. The children amazed me with their knowledge of the creatures. Their joy in the diversity of the marine ecosystem I found poignant and hopeful. Someone insisted the ocean would be fine, and doesn’t actually need saving. It’s us we’re doing the damage to – our way of life. It’s us that needs saving. The ocean, however it evolves, will be ocean.

What is ocean if not transitory, fickle, connecting? The most visible element of our hydrological cycle, its water wheels around our world as cloud, rain, river, mud, ice, snow, sap, sweat, tears and on, changing its composition, bringing people from one shore to another, as we were being taken from Liverpool to Douglas.

The pages began to fill up over the crossing. And I wondered how much we also need to learn this ability to change from the ocean. If what we love we love because of it reflecting something of us, I wonder if we might learn to love our own mutability, develop our capacity to adapt, trickle through the nooks and crannies of a sea wall. Can the scrawls, crossings out, mixed up handwritings and splurges also be seen as precious, threatening or under threat as the ocean the pages seek to capture?

I didn’t have conversations about Malcolm Lowry or his stories with the people I met. Instead I felt I was following his voyages more obliquely, with my fellow crew adding marginalia to the pages of the book, all underlining Lowry’s conviction that close contact with the natural world provides nourishment, connection and enrichment.

The book still has space for more. I like the idea of these spaces remaining, of the sense of the sea remaining incomplete, not overstuff with plastic or deadzones or trawlers or windfarms. We need an ocean that hasn’t been totally scribbled all over by humans. An ocean we can’t completely read, make use of, perceive as a resource rather than a living being that houses trillions of other living beings.

In December 2023, Leeds Beckett University hosted an exhibition of the works arising from this project